[Originally published at Permaculture News -- visit that site to see the comments.]

This Saturday, June 21st, is the fourth annual International Ragweed Day. For those who are allergic to ragweed pollen, the various varieties of ragweed (Ambrosia ssp.) can be a real bane of life. When someone you care about is swollen up like an itchy tomato and popping antihistamines and decongestants just to get out of bed in the morning, you might be tempted to want to eradicate the plant entirely. But is it all bad?

From an ecological perspective, and particularly in the Americas where it is native, we must first think of ragweed’s significance as a food for wildlife — notably quail, but also including some now-rare butterflies and moths. However, for those of us living in cities and towns where these creatures rarely venture anyway, any value to hypothetical wildlife is moot. Some herbalists may be inclined to follow up on ethnobotanical evidence that the Cherokee used ragweed to cure insect bites and pneumonia.

But for the rest of us permaculturalists, I think the most exciting way to simultaneously dispose of ragweed and put it to use is as a compost activator, particularly in sheet mulches. I should say here that all of my experimentation has been done with giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida) and not with common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), for a few simple reasons: it’s more common here in eastern Kansas, it’s easier to spot at a distance, and it’s much easier to harvest in quantity. Given a good thick stand of the stuff, one person can fill a pickup truck with giant ragweed in an hour!

showing the 6″ depth of the ragweed layer. This is one pickup truck load of ragweed.

the one whose soil test results are reported.

Note that the soil was already raised due to

excavation, and okra plants were already

established on the bare ground before the

sheet mulch was applied around them.

The brown matter layer is corn husks.

Giant ragweed is a close relative of sunflowers and sunchokes, and when its leaves first appear, they can be mistaken for the leaves of these more friendly plants. But as the plant matures, the leaves first divide into three lobes, then into five, and finally into seven, developing the characteristic ragged appearance that gives it its name. Also, the leaves are always parallel on the stem, so that from a distance the plant has a distinctive pagoda-like appearance. In my experience the leaves are also reliably a deep hunter-green color, even when neighboring foliage is yellowed from lack of nutrients. Once you’ve familiarized yourself with giant ragweed, you’ll find you can easily spot it at a distance.

The key thing to know about using ragweed in the farm or garden is when it blooms in your area. Here in USDA climate zone 6, it blooms in early September. That means that I can plan to harvest its copious green matter anytime from June through August without fear of spreading seeds or bringing home pollen. As an added bonus, pulling it up just before it blooms sets it back so much that even if it does grow back from the roots, it will not be able to bloom and set seed. Those who are allergic to the plant may want to protect their skin from its hairy leaves and stems while harvesting, though I haven’t heard of anyone having a skin reaction. I find that a firm two-handed tug is enough to uproot even the most stubborn and established plant.

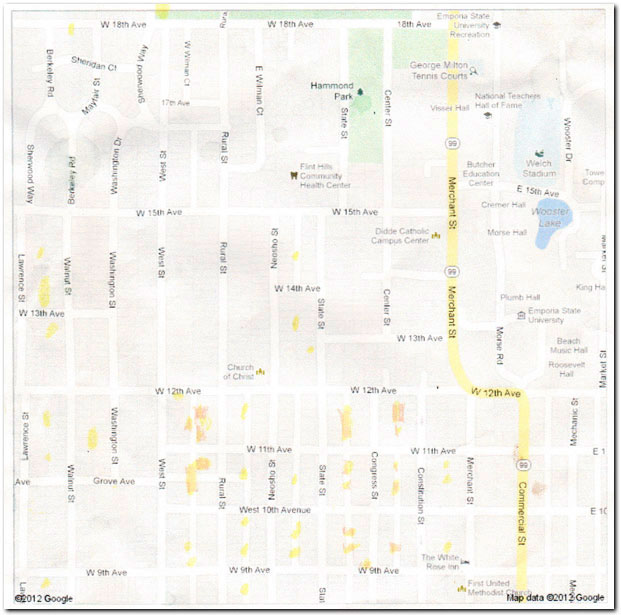

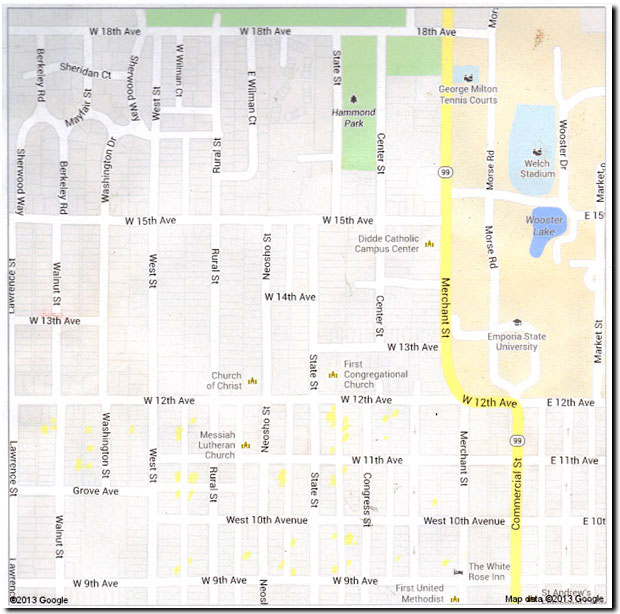

Over the past two years I have done a comprehensive survey of the area around my house and found not a single giant ragweed plant in anyone’s front yard, since even those who don’t know what it is know that it’s undesirable, but it can be found in abundance in alleyways, where no one cares if you pull it up and haul it away.

In June of 2012, after completing this survey, I harvested the largest stands for a mulching project, taking care to leave no survivors to set seed. Even so, when I returned the following year, the same stands had returned. This implies that seed can remain dormant for two years or more before germinating, which means any attempt at eliminating the plant must be persistent. Unfortunately I was not able to continue the experiment by pulling up the same stands the second year, so I leave that to you.

the middle indicate where I returned to eliminate the stands.

not noticeably smaller than the previous year.

Once harvested, the ragweed stems and leaves can be used in a traditional hot compost, but given their large size (some well over two meters) and their fibrous nature, they are better used as green matter in a sheet mulch, where they can be laid down whole to minimize labor. I have had great success with this technique year after year. The earthworms love it, and it breaks down completely by spring, if not earlier. After allowing a 3-6” (7-15cm) deep layer of ragweed to wilt to ensure it is dead, thoroughly rehydrate the green layer with water before adding a brown layer on top; otherwise it will mummify and take much longer to break down.

My soil tests before and after sheet mulching with ragweed show a doubling of organic matter (1.5 to 2.9%), a modest increase in nitrates (5 to 6 ppm) and more significant increases in phosphorus (20 to 81 pm) and potassium (294 to 516 ppm). These figures are from the same location, with ragweed and dead tree leaves as the only amendments, applied to the surface with no tilling. As I reported in an earlier article, comfrey produces much more impressive results, but ragweed has the benefit of being free for the taking, and the more you harvest, the less noxious pollen will be in your neighborhood!

I hope that my success with putting this unwanted and medically harmful plant to constructive use will inspire you to do the same. Please let me know if you’re giving it a try!

- Log in to post comments

Comments